The Universe's First Cinema

Camera Obscura—Latin for "dark chamber"—is not just a photographic technique. It is the fundamental optical principle that underlies all of visual perception, the very mechanism by which light becomes sight, reality becomes image, and the external world enters consciousness.

For over two millennia, this phenomenon has captivated philosophers, artists, and scientists. Aristotle observed it in the 4th century BCE. Leonardo da Vinci explored its mysteries during the Renaissance. Yet today, in our age of digital acceleration and instant capture, Camera Obscura offers something revolutionary: a return to the essential nature of seeing itself.

The principle is profound in its simplicity: light passing through a small aperture projects an inverted image of the outside world onto the opposite surface. No lens required. No digital sensor. No algorithm. Just light, space, and the fundamental laws of optics that govern how photons travel through our universe.

Above the River and Under the Sky — Inn River, Innsbruck, Austria, 2026

Light: The Cosmic Teacher

Every photon of sunlight touching my Camera Obscura has traveled for 8 minutes and 19.67 seconds from the Sun's surface—a journey of 93 million miles at 186,000 miles per second. This is not metaphor. This is physics made poetry.

When I make an 8-second exposure, I collaborate with light that began its journey over 8 minutes ago. This creates temporal layering: cosmic patience meeting human presence, revealing how artistic practice bridges scientific precision with perceptual experience.

The Nature of Light in Camera Obscura

Light doesn't just illuminate—light writes. In Camera Obscura, light becomes the artist. It draws directly onto photosensitive paper, creating unique chromogenic negatives through pure chemistry: silver halide crystals responding to photons without mediation, without digital translation, without the intervention of any algorithm.

This is luz, lumière, Licht—light in its primordial role as information carrier, as reality's messenger, as the fundamental force that makes vision possible. Camera Obscura strips away everything except this essential transaction: photons meeting chemistry, energy becoming form, time crystallizing into image.

The Philosophy of Eight Seconds

My Camera Obscura practice centers on 8 seconds—not just as exposure time, but as complete temporal cycle revealing infinity within limitation. Against digital acceleration fragmenting attention into microseconds, I offer 8 seconds of temporal breathing where past, present, and future interweave.

The Lazy Eight: When Numbers Dream

When the number 8 lies down for a nap, it transforms into the infinity symbol (∞)—the lemniscate. This simple rotation from vertical to horizontal represents one of philosophy's most profound insights: that limitation and limitlessness are not opposites, but dance partners.

Each 8-second exposure captures one complete journey around this "Lazy Eight"—a perfect cycle of light and time that contains everything and never ends.

Temporal Resistance in the Digital Age

In our acceleration-obsessed culture, slowing down for 8 seconds becomes an act of rebellion. While the world fragments into microsecond attention spans, I create work that demands presence. My 8-second exposures function as what philosopher Henri Bergson called "durée"—lived duration where memory and sensation interpenetrate.

The blur in my work isn't technical failure; it's visual evidence of Bergson's "interpenetration of consciousness and time." The photographic paper accumulates light the way memory accumulates experience—not as discrete snapshots but as layered duration.

Motiongraph #140 — Elbphilharmonie, River Elbe, Hamburg, June 2018

The Mobile Camera Obscura: Setting Light in Motion

The revelation came in 2012 in New York. Riding the subway through a tunnel, the train lights went off. External light flickered through windows—and suddenly I understood: motion is time made visible. I needed to set the Camera Obscura in motion.

The Boat

My Camera Obscura boat transforms European waterways into floating darkrooms. Drifting on the Spree, the Elbe, the Seine—I work in complete darkness, hanging chromogenic paper by memory, counting eight seconds while the world flows past. The river's movement becomes part of the image, water's motion writing itself into the chemistry.

The Van

Converted over three years, my Camera Obscura van allows me to photograph from roads, bridges, and alpine passages. Driving slowly while making exposures, I capture the landscape's temporal dimension—not frozen moments but flowing duration. The vehicle becomes both camera and studio, darkroom and observatory.

The Walking Camera

My 8x10 Walking Camera Obscura, shot from the belly, reaches places larger vehicles cannot access. Standing in Camargue searching for Van Gogh's trees, or positioned on alpine trails—this portable darkroom brings Camera Obscura's magic to intimate spaces where only the body can go.

The Process

Inside these mobile darkrooms, I work in complete darkness. After hundreds of exposures, my hands know the space absolutely. I cut photographic paper by touch, hang it by memory, count eight seconds—not seven, not nine—because eight seconds is my personal portal to staying present, to temporal breathing, to collaboration with cosmic light.

Looking for Van Gogh's Trees — Camargue, France, July 2023

Motiongraphs: Records of Time in Motion

I call my works Motiongraphs—not photographs, because they don't merely record light. They record time collaborating with light in the motion of life. Each piece is a unique chromogenic paper negative, created through direct exposure without film, without digital mediation, without post-production.

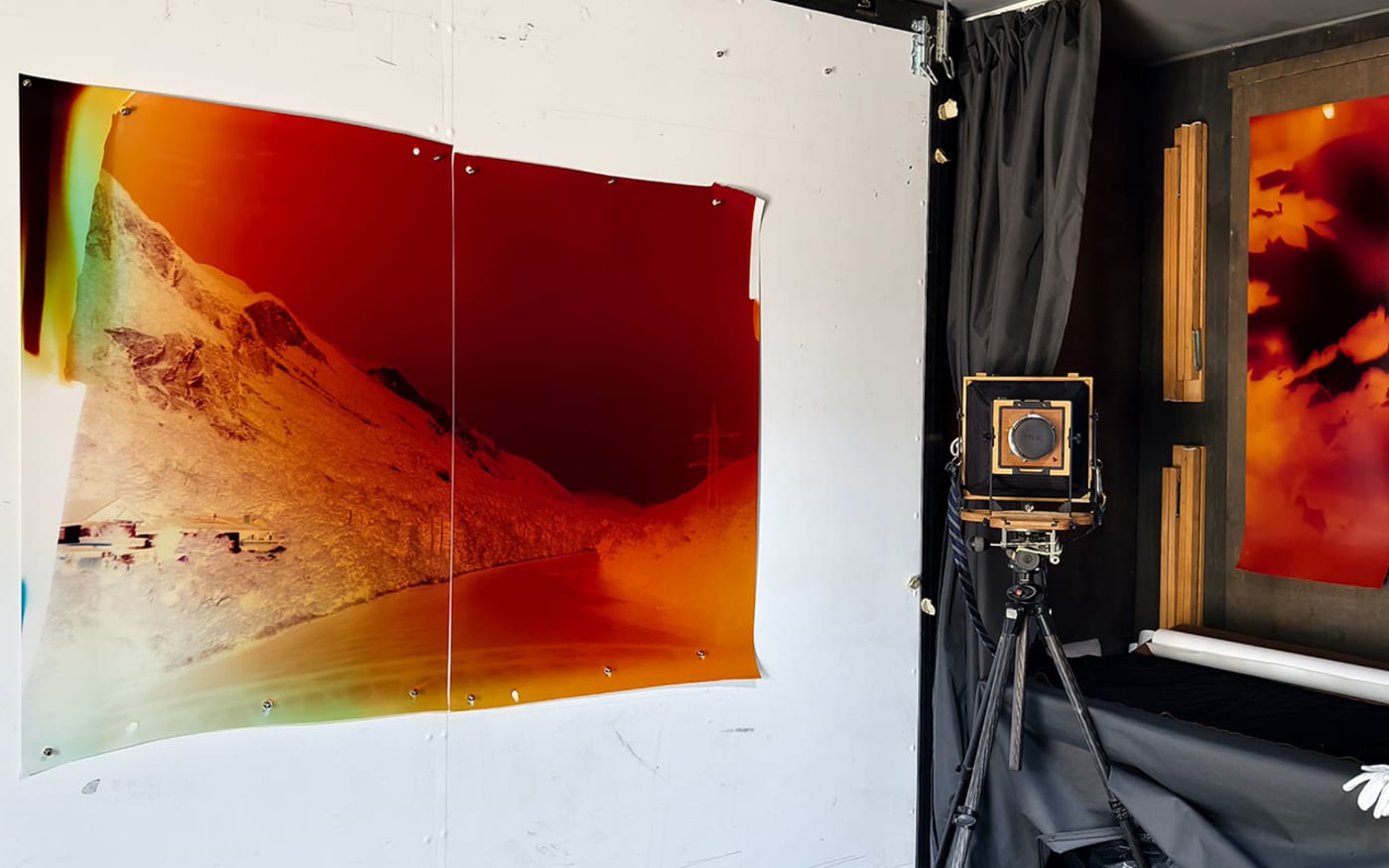

The Setup

The entire process—including setup, capturing, and developing—can take several hours or days of preparation. I have worked exclusively on this process since 2014 and have made only about 400 Motiongraphs to date. Inside my mobile Camera Obscura, I work in complete darkness. Large-format color photographic paper—sometimes 127 x 204 cm (50 x 80 inches)—is positioned where light will fall through the aperture.

The Exposure

For exactly 8 seconds, I open the aperture. During this time, the vehicle moves, water flows, shadows shift, light quality changes. All of this motion—cosmic, terrestrial, atmospheric, luminous—becomes part of the artwork.

The Chemistry

Silver halide crystals in the photographic paper respond directly to photons—pure chemistry and physics. No sensor, no algorithm intervenes. The paper's grain structure holds traces of humidity, temperature, even my breathing.

The Negative

What emerges is a chromogenic paper negative: colors inverted, orange where blue existed, magenta where green appeared. I present these negatives as final works because they show how light truly writes itself in chemistry—light's own handwriting.

Why Blur Reveals Truth

The blur in my work isn't aesthetic choice or technical failure—it's truth. We think we see the world sharply, frozen in clear moments, but that's an illusion created by our brain's processing. Our perception is continuous flow. The Motiongraph reveals what we actually experience but lose in our snapshot way of seeing.

Motion and stillness coexist. The distant objects appear sharp because they move slowly relative to my camera, while nearby objects blur because they pass quickly. This reveals the relativity of motion, the way speed and distance collaborate to create our experience of space and time.

Beyond Representation: Consciousness Made Visible

My Camera Obscura work doesn't show you motion and light—it awakens you to the fact that motion and light are what create the very possibility of seeing, of conscious experience itself.

Each Motiongraph is a consciousness experiment. You don't see my artwork—you discover how your mind creates temporal reality. In those 8 seconds of exposure, motion becomes time, and time becomes visible as the fundamental force that creates all visual experience.

This is time teaching you about the deepest nature of conscious experience itself.

Camera Obscura Through History

Camera Obscura's lineage spans millennia, connecting my contemporary practice to humanity's oldest investigations into the nature of light and perception.

Ancient Observations (4th Century BCE)

Aristotle observed Camera Obscura principles while studying light passing through leaves during solar eclipses, noting how circular apertures created crescent-shaped images of the eclipsed sun.

Renaissance Exploration (15th-16th Century)

Leonardo da Vinci extensively documented Camera Obscura in his notebooks, recognizing it as analogous to the human eye. Renaissance artists used large Camera Obscura rooms to achieve unprecedented accuracy in perspective and proportion.

Scientific Revolution (17th Century)

Johannes Kepler coined the term "Camera Obscura" and used it for astronomical observations. The device became fundamental to understanding optics and the nature of light itself.

Birth of Photography (19th Century)

Nicéphore Niépce, Louis Daguerre, William Henry Fox Talbot—photography's pioneers all worked with Camera Obscura principles, discovering how to make the projected image permanent through chemistry.

Contemporary Renaissance (21st Century)

Today, Camera Obscura experiences a renaissance as artists rediscover its contemplative power. In our digital age of instant capture, Camera Obscura offers something radical: slowness as resistance, presence as practice, duration as revelation.

Why Camera Obscura Matters Now

In the 200th year of photography's invention, we face a paradox: we've never taken more photographs, yet we've never been less present to what we see. Digital photography offers instant gratification but removes us from the fundamental mystery of light becoming image.

Camera Obscura as Antidote to Digital Acceleration

While digital cameras fragment time into microseconds and smartphones transform seeing into sharing, Camera Obscura insists on duration. It demands presence. It refuses to be hurried. In this refusal lies its radical power: the assertion that consciousness deserves more than fragments, that experience requires duration, that seeing demands time.

Return to Pure Perception

For the first 10 weeks of life, newborns see the world upside down and reversed—just like Camera Obscura. Their brains haven't yet learned to "correct" the inverted image. This raw, unfiltered gaze is what I chase in my work: perception before interpretation, seeing before knowing, presence before memory.

Camera Obscura returns us to this primordial vision. Inside the darkened chamber, watching the upside-down world project itself onto paper, we experience seeing as it truly is: not a passive reception but an active participation in light's creative power.

Unique in an Age of Infinite Reproduction

Each Motiongraph is ontologically unique. The exact configuration of light, motion, atmospheric conditions, and temporal flow captured in those 8 seconds will never repeat. In an age of AI-generated images and infinite digital reproduction, handmade unique objects created through direct light collaboration gain significance precisely because they cannot be duplicated.

Time never flows identically twice. Each photograph I make has its own singular existence and its own destiny.

The Art of Temporal Breathing

Camera Obscura taught me that when we stop rushing and give ourselves the gift of 8 seconds of complete attention, we don't get less—we get everything. We get the infinite hiding inside every ordinary moment.

My obligation as an artist is not only to create artwork but to pass it along to people who might enjoy it, who might be moved by it, who might slow down because of it. Each piece is an invitation: to step back into temporal flow, to experience duration rather than instants, to discover that consciousness and motion are constantly creating the very possibility of being present, moment by moment, through their eternal partnership.

This is why Camera Obscura art matters. This is why 8-second collaborations with time and motion are revolutionary. This is why each piece contains not just an image, but a doorway into the deepest mysteries of existence itself.

My Camera Obscura keeps moving because life keeps flowing.

I simply continue being—present.